Blog

Filling the void: wastewater data and the end of the public health emergency

June 7, 2023

With the end of the public health emergency declaration on May 11th, the COVID-19 data landscape in the US will change drastically, and not for the better. States have been pulling back on publicly reporting data for a while now, this trend accelerating in recent weeks with Iowa being the first state to stop any reporting of COVID-19 case data to the CDC.

Reporting of hospitalization data is planned to continue in the short term, but likely at a reduced frequency which means less timely data. So where does this leave us, and how does wastewater data fit in the larger picture moving forward?

Relying on hospitalizations and deaths to determine what to do can be sort of like saying that you are going to wait until you’re fired or the company is bankrupt before determining whether you need to improve your job performance.

Bruce Y. Lee CDC Will Stop Tracking Covid-19 Community Levels, Here Are The Problems

All public health data types are not created equal, and each fills a different need for timeliness, completeness, and impact. While hospitalizations and deaths are high-impact data sources and easy for everyone to understand, they are late metrics. By the time a surge is detected in hospitalizations or deaths, the infections that lead to future hospitalizations and deaths have already occurred. In contrast, wastewater data is an early-indicator of disease activity, and changes in wastewater levels and trends happen before changes in metrics of hospitalizations and death.

Can wastewater tell us anything about these other data sources?

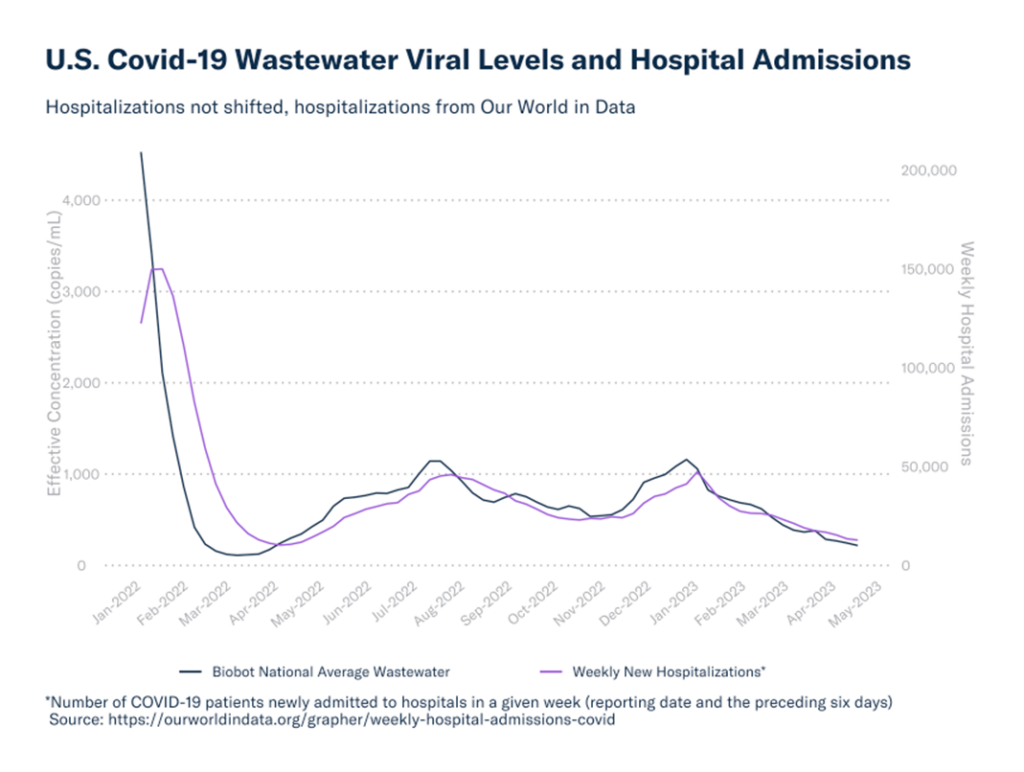

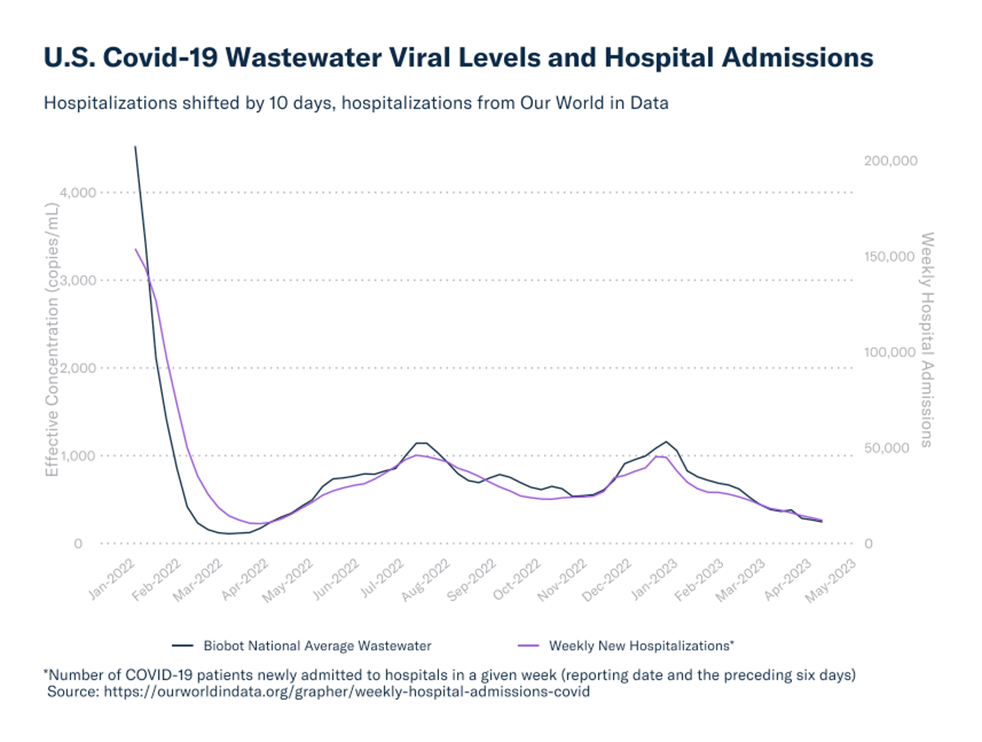

Wastewater on its own can provide valuable information on the spread of the virus—whether levels are high or low, and if they are increasing or decreasing. But importantly, wastewater data also aligns very well with COVID-19 hospital admissions data. People infected with SARS-CoV-2 start shedding very early in their infection (which we can see in wastewater), while hospitalization occurs typically in the second week of their infection. From a data analysis perspective, this means that we would expect peaks and troughs to occur sooner in wastewater than they do for hospitalizations, which we see when we plot the data. Visually, this is easiest to observe when the data peaks—you can see this in July 2022, when the wastewater levels peaked the week of July 13th and hospitalizations peak the week of July 27th, and in January 2023 when wastewater peaked the week of December 28th and hospitalizations the week of January 4th.

If you shift the hospitalization curve back by 10 days to account for the expected hospitalization delay, these two curves line up exceptionally well. This strong correlation over such a long time period (January 2022-April 2023) shows the power of wastewater to accurately reflect trends and provide an early indicator of when peaks and troughs in hospitalizations are likely to occur in the near future.

Wastewater is an efficient way to track emerging and circulating variants

Tracking emerging variants is crucial for many reasons such as informing vaccine formulation and assessing whether current treatments are still effective (for instance, the FDA limited the use of some monoclonal antibodies because they were not effective against the Omicron variant). Tracking variants can be done through genomic sequencing of either clinical or wastewater samples. Sequencing of clinical samples is expensive due to the large number of individual samples required, and as home testing has increased, the number of samples available for clinical sequencing has decreased, making this option likely far less representative of the population as a whole. On the other hand, sequencing wastewater samples is a cost-effective method of tracking variant proportions over time within communities. It is versatile, and can be used at a small scale to show what is circulating in a single county, and at a larger scale to show what is happening nationally.

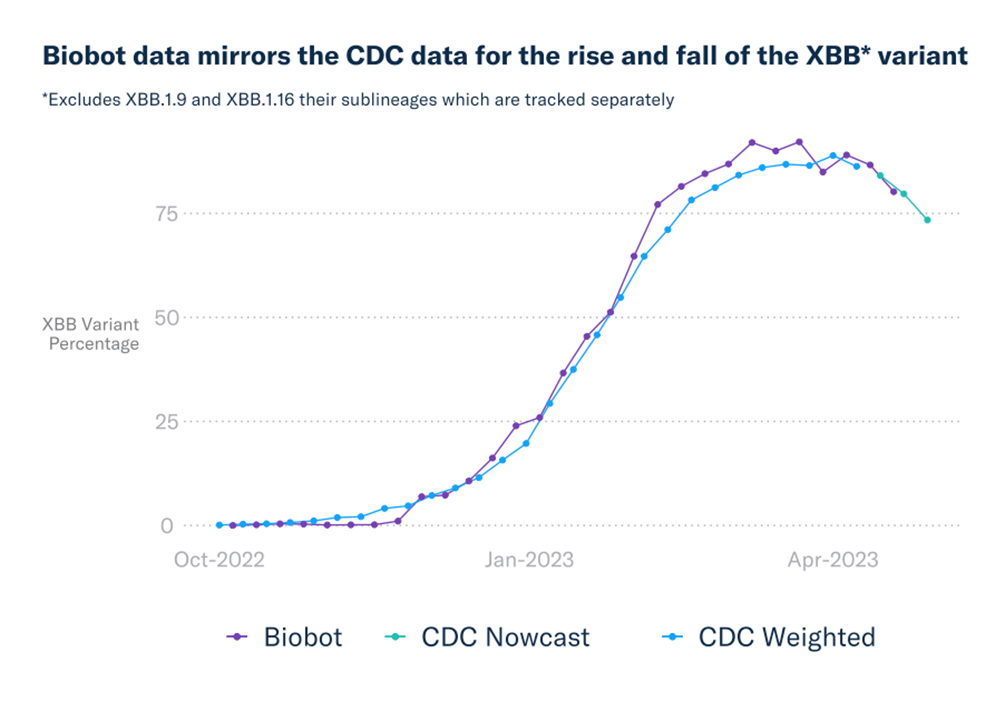

Tracking variants through wastewater analysis is cost effective, but even more importantly, it works, and works really well! The plot below highlights a number of things, the first being that Biobot’s calculated wastewater national average of variants tracks the rise and fall of the CDC’s XBB variant family extremely closely. (Of note, in this visualization the XBB.1.9 and XBB.1.16 variants are excluded from both the Biobot and CDC data as they are being tracked separately.) The second point is that wastewater sequencing data can be very timely. The “CDC Nowcast” lines are predictions of what the data will show at that time, not reflections of existing data. The Biobot line is all based on existing measured wastewater data, and you can see that it extends further forward in time than the CDC’s ‘weighted’ data, which represents their measured data rather than their modeled estimates. Effectively wastewater data helps tell an accurate data-rich story of real real-time that have historically been only predictions.

Wastewater is a versatile data source

As we’ve seen, information gained through wastewater-based epidemiology can provide information about a lot more than just current levels and trends in a community. It can provide an indication of where hospitalizations will be trending in the near future, and provide insights into how the severity of the pandemic has changed over time. It can be used to track emerging variants, and help clinicians and regulators make decisions about what treatments to use. The field of wastewater-based epidemiology is evolving, and advances in analytic methodology and modeling will continue to enhance the value of wastewater data for public health officials and communities alike. While the PHE has come to an end, COVID-19 is here to stay—luckily wastewater will continue to be a rich data source, providing reliable data, and be the best way to monitor COVID-19 levels and variant trends as we move forward.

Written by Biobot Analytics

Biobot provides wastewater epidemiology data & analysis to help governments & businesses focus on public health efforts and improve lives.