Blog

What makes a good wastewater-based epidemiology target?

March 21, 2020

Sewage is a community-level urine and stool sample, how do we decide what to look for?

At Biobot Analytics, we’re building a platform to measure population health by analyzing human chemical and biological information collected in our sewers. We’ve applied our technology to measure the scope of the opioid epidemic, and are now rolling out methods to track the spread of COVID-19 through sewage.

The idea behind our technology is simple: everybody pees (and poops, hopefully) every day. When you use the toilet, you’re excreting valuable health information. The bacteria, viruses, and chemical metabolites that you shed provide a readout of your health. Think of it like this: it’s like going to the doctor and giving a urine or stool sample for diagnostic tests, but instead of measuring just one individual, we can measure an entire community. Sewage is a community-level urine and stool sample, and we can leverage that to track disease and respond quickly to epidemics.

In fact, there’s a whole scientific field behind this idea that’s called wastewater-based epidemiology (WBE). The first two major applications of WBE were a European network called SCORE which monitors national drug consumption and environmental surveillance for poliovirus, both established around 10 years ago.

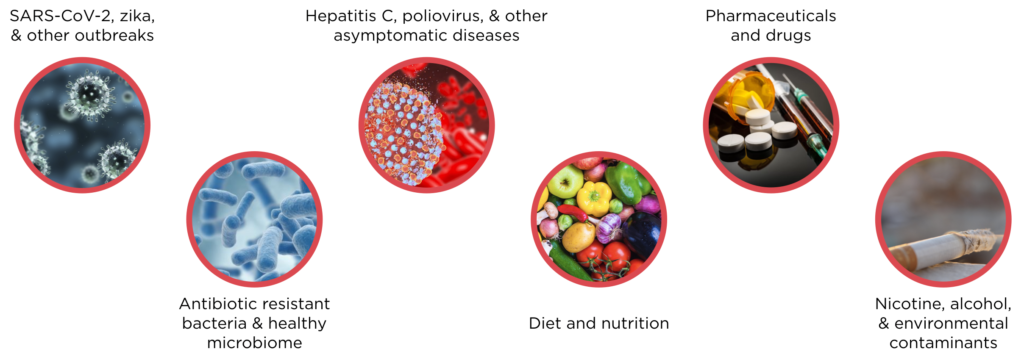

But how do we decide what to look for in sewage? At Biobot, we think of good targets for wastewater-based epidemiology as having four key features:

- There needs to be a clear biological or chemical marker for the disease or target of interest. If you want to monitor something, you have to be able to measure it. It doesn’t matter if the marker is a chemical, bacteria, or virus, as long as it’s specific to the disease you’re trying to measure. In the case of infectious diseases, the marker is usually just the bacteria or virus causing the disease, which can be detected through DNA sequencing analysis. For opioids, we use mass spectrometry analysis to measure the chemically modified versions of the opioid drugs after they’ve been consumed, metabolized by our liver, and excreted in urine.

- The marker needs to be excreted in urine or stool. Because we’re looking in sewage, whatever marker we’re measuring needs to end up there. Most drugs and foods that we consume leave a chemical signature in our urine, and many infectious diseases can be measured in stool. For example, recent studies have shown that the new SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 is excreted in stool. In contrast, the bacteria that causes strep throat isn’t shed in stool, so strep wouldn’t be a good target for sewage-based monitoring.

- There is a large asymptomatic or untested population. Most public health monitoring systems rely on hospital-based tracking, so individuals who don’t get care also don’t get counted. But since everybody uses their toilet, everybody gets counted in sewage. That makes sewage-based health monitoring an important complementary data source to existing public health statistics. It counts people who are asymptomatic or whose symptoms are too mild to prompt a visit to the doctor, and it also includes people who might not seek care because they are uninsured, undocumented, face stigma, or otherwise have barriers to accessing healthcare. COVID-19 seems to fit the bill here, as we’re now learning that the virus may be transmitted even by people who are not showing symptoms. Also, because access to diagnostic testing remains very limited, the data we have on this disease’s spread is likely to be drastically underestimating the actual extent of the epidemic.

- Public health and city officials can act on the information provided. At Biobot, our most important consideration when deciding what to monitor in sewage is that it’ll be useful to public health officials and will provide information that helps them make decisions. For opioids, identifying priority substances helps public officials tailor their harm reduction and educational outreach efforts. In the case of COVID-19, tracking the spread of disease to new cities helps officials get ahead of the curve, prepare hospitals for an influx of cases, and provide decision support for determining the timing and severity of public health interventions. Sewage-based monitoring will also be helpful to see when new waves of the disease re-emerge, if COVID-19 does indeed have a cyclical pattern.

As you can see, COVID-19 has all of the characteristics that make it particularly suitable for wastewater-based monitoring. That’s why we’re so excited to announce the launch of our COVID-19 program, partnering with city officials to test wastewater facility samples for the SARS-CoV-2 virus to better understand and respond to this growing epidemic. Click on the link to find out more and learn how you can get involved!

Written by Claire Duvallet, PhD

Biobot Analytics’ Founding Staff Data Scientist